You Should Put a Codex in Your Pocket Instead of Your Phone

Right now, most of us have a particular, very familiar gesture that happens in liminal spaces... a checkout, at a stoplight, the daycare pickup line…we reach for our phone. What if, every time you instinctively reached for a moment of phone distraction -- you reached for your codex instead?

Stop scrolling and start thinking

I like to think I know my audience — especially since I try to write things that I would want to read. I suspect most people clicked on this link in the hopes of finding another tool or process that might defend against the aggressive addiction-preying apps on their phone. “Low screen time” is as much a health bragging point as “low blood pressure”, but it’s hard to resist something that is tracking you, selling to you, and is actually useful or entertaining just enough to make you feel like you can’t live without it.

I’m not going to tell you to get rid of your phone. I’m not going to pretend that’s even possible for most of us living in this culture. It’s a well-known aspect of addiction that just cutting out a habit “cold turkey” rarely works — it’s far more effective to find something to replace the addictive substance.*

That’s what I’m going to do. I’m going to suggest something simple, accessible, affordable, and with a proven track record against the scroll:

You need a pocket codex.

A what? I imagine I hear my readers say.

The Amazing History of the Codex

You’ve probably come across this word a time or two in your life, especially if you’re a D&D nerd, a lawyer, a programmer, or the like.

Forget all that. This is not that kind of codex.

The earliest recorded use was in 291 A.D. by a Roman lawyer named Gregorianus. You can imagine him as the guy at the office who’s always gotta be a step ahead with the latest tech or app — the first one who had a Palm Pilot, or a smartwatch, or the first who used ChatGPT to help write a letter.

Back in 291, just like today, there were a lot of lawyers talking a lot of law. And most of them would carry their records and law books on scrolls, carried around in big round boxes called capsae:

Now, scrolls were awesome, because you could write on long sheets that could be rolled up and stored, as opposed to fragile clay tablets or ephemeral wax or other forms of writing at the time.

But they had their downsides. For one thing, you could only write on one side of the scroll (lest you risk smudging the writing). As the mosaic above shows, carrying around even just some of your scrolls was pretty inconvenient (I’m guessing that much like today they used unpaid interns to lug around the documents).

Anecdotally, Gregorianus strolled into a meeting without any capsa at all, not even a single scroll in his hand. Instead, he seemed to be holding a block of wood — which is what the word codex means, as it happens.

Then I imagine he blew everyone’s mind, because he opened the block of wood. It turned out the block was sliced into thin sheets — we would think of them as pages — and there, on the first page, was the statement of one of his clients**

Then he blew their minds again — because when he flipped that sheet over, there was writing on the back, as well.

Look, I get that this isn’t a big deal to us — seems obvious, right? I’m trying to think of an analogy, but the only kind of one-side one-use scroll I can think of in modern times is toilet paper, and that seems like a crappy metaphor.

To the people of the time, this was amazing. And it got adopted in many, many ways, and still is. I’m betting at some point today you saw a folder, a brochure, a notebook, a novel, a textbook. We’ve made up all those terms to delineate the type, size, or intended use of the same category of object: codex.

Basically, it was used to describe the type of written record that’s not a scroll.

What does this have to do with less screen time on my phone?

I’m glad you asked.

You may have noticed that there aren’t a lot of scrolls around your house, and it’s really hard to find any designer capsae. Tell a contractor you want a pegmata addition to your house with loculamenta on the walls and you may get a very funny look.

Tell her you want to have a library with shelves? No problem.

That’s why I think a codex can be the key to lowering your screen time — it’s already proven to be a good replacement for the scroll.

There’s a nice little fold known by different names — “fold & gather”, “1/8th page zine”, “pocketmod” — that makes a miniature codex that will fit into most pockets, either on your person or in a handbag of some kind.

When I say easy, I mean: easy:

https://youtu.be/kxoylaXZNQI?si=NMg2EZDIhnUJ-bgg

If you’re waiting for me to give the “one guaranteed way to use this notebook to stop using your phone”, I’m not going to.

I’m going to give you seven:

- Bujo Running Log: My biggest beef with bullet journaling is the idea that you spend all your time with your notebook open, keeping a record of your day. Put a cheap clicker pen in your pocket with this codex, and now instead of dragging out a big notebook and paging through it, you pull out your codex, scribble a note, and put it away.

- Time tracking: either for client work or just to follow the ubiquitous advice from any ”How to feel less stressed about time” coach, you can scribble a little time-scale down the side of each page and write in how you spend that time. There are eight pages (remember, you can write on the back!) so you have one codex, one week: easy.

- Anything-Else Tracking: Want to track your meals without being asked to upgrade an app? The codex can do it. Track your media. Write the names of the people you meet. Make a list of the vinyl records your grandson wants, or the stats from your other grandson’s basketball games.

- Gratitude: This may just be me, but I find that the usefulness of a “gratitude journal” is matched by my grumpiness about actually doing a gratitude journal. This makes it easy and accessible.

- Squirrels & Rabbit Holes Successfully Avoided: this one goes out to my ADHDers especially: the codex can help you focus, because when a squirrel tries to lure you down a rabbit hole***, you can write down what almost pulled you away from what you want to focus on, and your brain will know it’s safe for later.

- Sketching: Almost all of us have years of training and experience in sketching either our surroundings or our original creations. I’m speaking, of course, of our first five (or if we’re lucky, more) years of life, when we scrawled little things on paper and had the people most important to us exclaim in pleasure and pride and hang them on the big box where yummy stuff lives.

You may be more self-conscious now, but you don’t have to share it or hang it on the fridge. Look up “the mental benefits of doodling”, put a codex and pen in your pocket, and let your artist flag fly. - Eight-Images Journaling: This is a callback to a journaling method I mentioned in my last article — Ash Parsons suggested “ten images” from your day, just written down either in full or in brief, as a good way to journal without pressure. The pocket codex adds convenience, accessibility, and immediacy to the idea — instead of having to think them all up in the evening, you can make quick notes of them during the day, and then in the evening just the act of looking at them will cause you to reflect — and then, whether you write about them, draw them, or angrily scribble them out with a red sharpie, you’ve gotten a benefit of journaling.

You might get the idea by now — there’s a zillion ways to use a little notebook in your pocket, and you don’t have to pick just one. You don’t have to carry just one. You also don’t have to keep them — though I suggest you do. I don’t think Gregorianus really thought that people would be writing about his client statements millennia down the road — but we are. You never know who or when that little codex may go from trifle to treasure.

Because codices were handwritten, there were few copies of any single codex, and sometimes only a single copy. - Merriam Webster

Ya gotta use it — and there’s a great way to ensure you do.

And it’s dead simple:

Wherever you carry your phone — put the pen and codex there instead.

You don’t have to get rid of your phone. You don’t even have to make it inconveniently inaccessible (though that might be a good idea too).

But wherever your phone usually lives — and you know where that is — put the codex and a pen there instead.

It leverages a habit and muscle memory most of us already have!

Right now, most of us have a particular, very familiar gesture that happens in liminal spaces (when we’re in between things) or any time we have to wait for a time. In a checkout, at a stoplight, the daycare pickup line…we reach for our phone.

What if, every time you instinctively reached for a moment of distraction from your phone, you found instead your gratitude codex?

Even if you grumbled, cursed that silly Gray guy on Medium, and reached for your phone instead — for a moment, your brain was thinking about gratitude.

Or thinking about what you’re doing right now.

Or thinking about something you read, or watched, or want to.

The point is that you are interrupting your phone habit with something that is both engaging and easy. You could add on little ceremonies and rituals, if you wanted:

- if I reach for the codex, I have to try and remember the last thing I wrote in it. If I’m right, I win; if not, I have to write something worth remembering.

- if I reach for the codex, I have to write at least one word (one line, one letter, whatever)

- if I reach for the codex, I don’t have to open it or write anything — but I have to stand up and start walking

…and then let yourself reach for your phone instead.

It’s an investment in yourself

It also makes an impression on other people — if you are talking with someone and they say something you want to remember, when you pull out a pen and paper instead of risking distraction of the phone, it makes a difference. Especially if it’s pen and paper — because you are making an indelible mark on single-use paper about them. That’s a very different feeling than having a phone scan your biz card and lose your name amongst a zillion other contacts in the cloud.

One other fun thing about the codex is that it’s infinitely customizable.

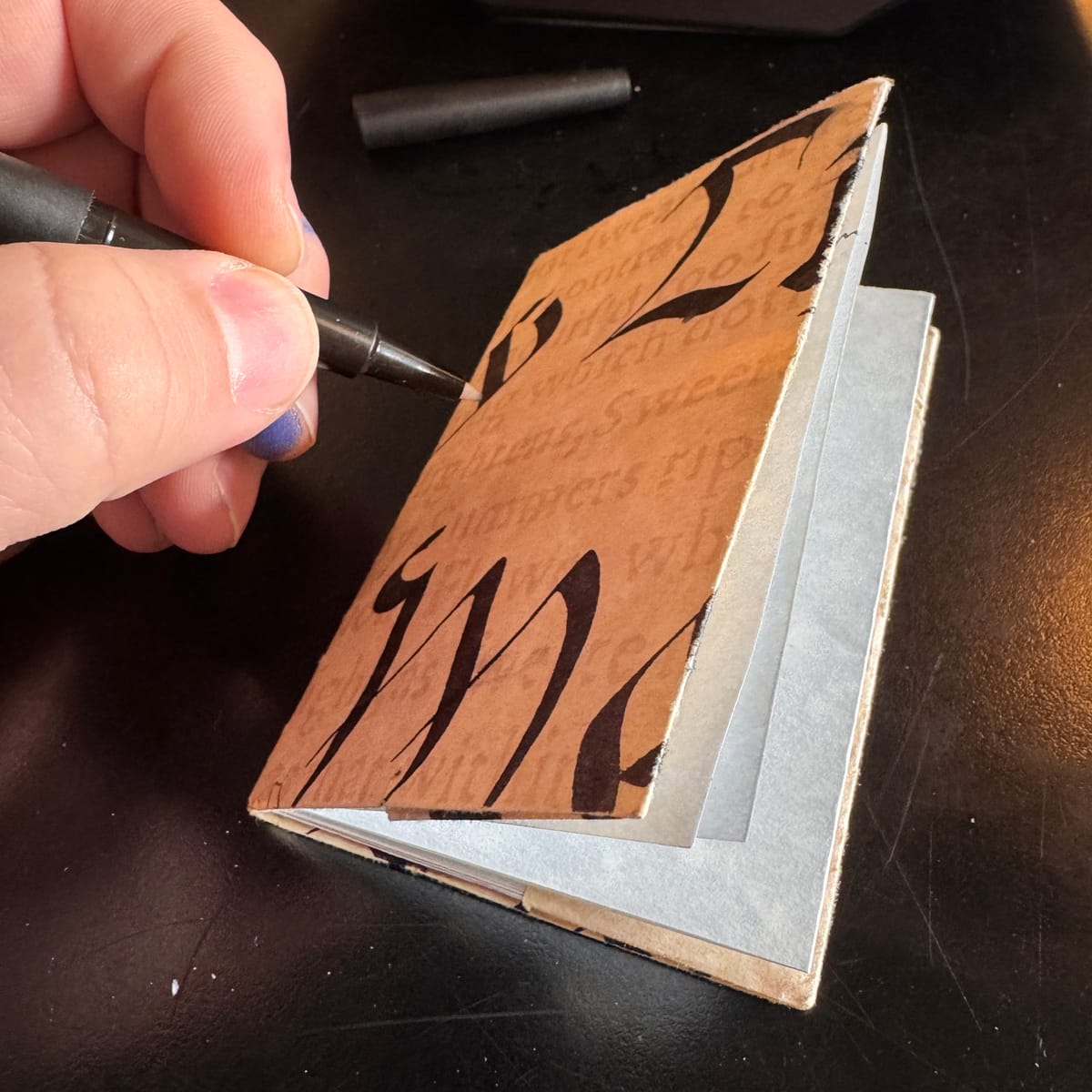

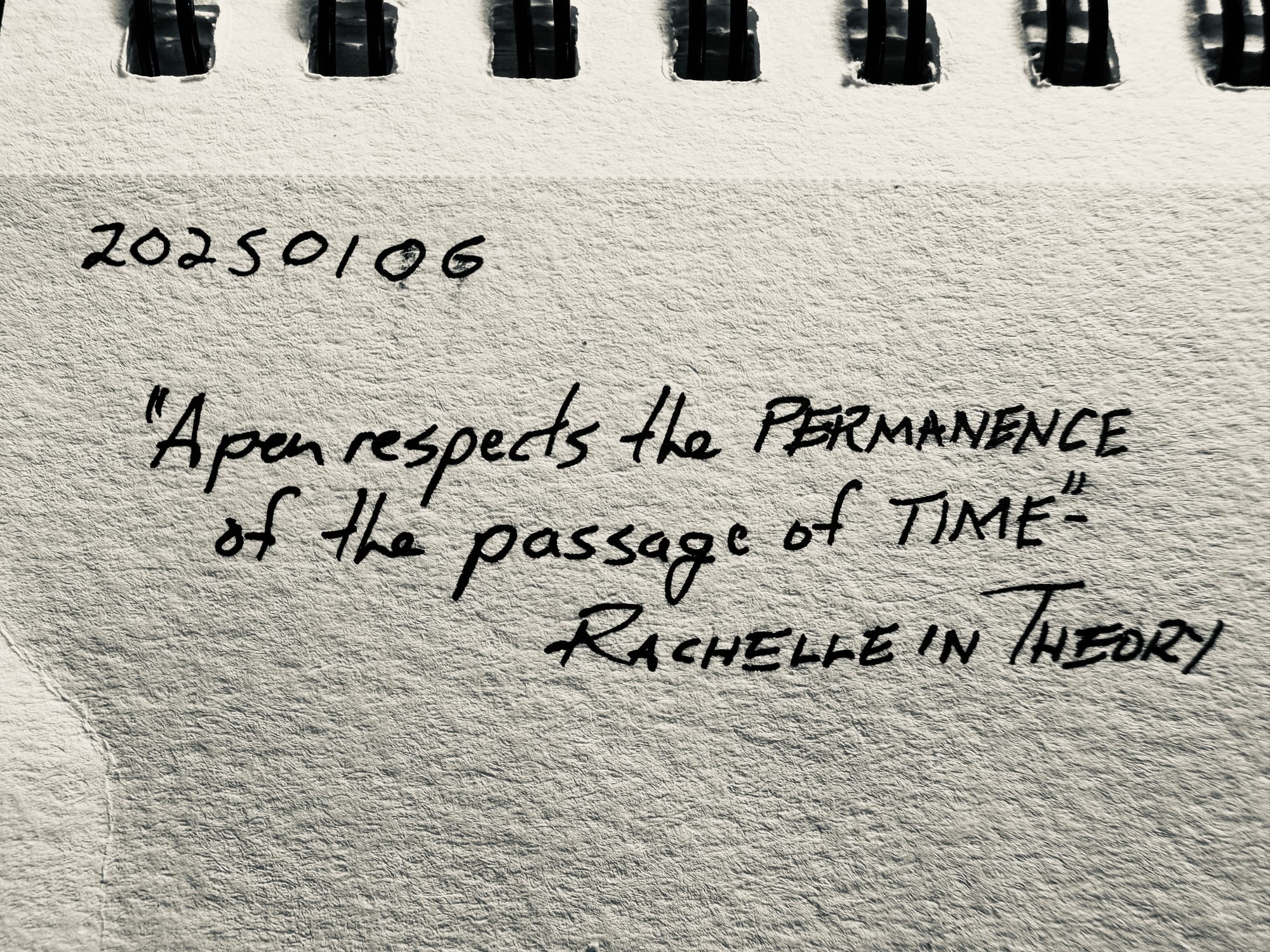

You can buy or create fine leather covers for the little zine. You can use fancy paper, or themed paper, either bought at a stationery store or printed out. You can put stickers on it, or stamp it, or singe the edges with a cigar and sprinkle 25 year MacAllan whiskey on the pages. My own current codex is a folded piece of fine resume paper (with a kind of impressionist shading to it) with a folded cover made of vellum with some of my calligraphy practice on it.

This is my codex. There are many like it. But this one is mine.

If you like the idea of a codex and other paper-based personal magic and rituals, you might enjoy my papermancy.art blog!

* While I can’t unreservedly recommend James Clear’s Atomic Habits, he does a good job of laying out one of the most well-known examples of this, heroin addiction recovery in Vietnam vets.

** While some of this is obviously speculation, this part isn’t, because some of Gregorianus’ codex we still have as part of the more-well-known Justinian Codex.

*** if you find this confusing, don’t worry — it’s an ADHD thing.